In the New World, “yokes” are mentioned a number of times in the Book of Mormon:

And

they did humble themselves even to the dust, subjecting themselves to the yoke

of bondage, submitting themselves to be smitten, and to be driven to and fro,

and burdened, according to the desires of their enemies. (Mosiah 21:13)

O

ye that are bound down under a foolish and a vain hope, why do ye yoke

yourselves with such foolish things? Why do ye look for a Christ? For no man

can know of anything which is to come. (Alma 30:13)

Yea,

they durst not make use of that which is their own lest they should offend

their priests, who do yoke them according to their desires, and have brought

them to believe, by their traditions and their dreams and their whims and their

visions and their pretended mysteries, that they should, if they did not do

according to their words, offend some unknown being, who they say is God-- a

being who never has been seen or known, who never was nor ever will be. (Alma

30:28)

Behold,

we have not come out to battle against you that we might shed your blood for

power; neither do we desire to bring any one to the yoke of bondage. But this

is the very cause for which ye have come against us; yea, and ye are angry with

us because of our religion. (Alma 44:2)

And

being thus prepared they supposed that they should easily overpower and subject

their brethren to the yoke of bondage, or slay and massacre them according to

their pleasure. (Alma 49:7)

And

it came to pass that he was exceedingly angry with his people, because he had

not obtained his desire over the Nephites; he had not subjected them to the

yoke of bondage. (Alma 49:26)

We

would subject ourselves to the yoke of bondage if it were requisite with the

justice of God, or if he should command us so to do. (Alma 61:12)

“Yokes” were indeed part of the

material culture of Mesoamerican peoples during the time of the Book of Mormon.

Note the following:

Yokes

Yokes

are U-shaped stone objects. Contrary to what their popular name may suggest,

yokes could never have been used around the necks of large domesticated draft

animals, since these did not exist in pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica.

One

early hypothesis suggested they were placed around the necks of sacrificial victims.

It was only in the mid-20th century that the theory that these objects were

really ballgame belts gained widespread scholarly acceptance.

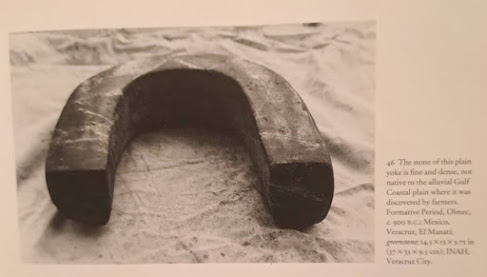

The

earliest documented standard-size yoke was recently recovered at the stie of El

Manatí in Mexico’s Gulf Coast state of Veracruz.

Reportedly,

it was placed above two adults buried seated facing each other. Unfortunately this

was an accidental find made by farmers, not archaeologists, so the yoke’s

context remains hearsay. The surface of the dark, greenish-black stone is

smooth and undecorated (fig. 46). It has slightly spreading open ends and is

not symmetrical, one side being slightly shorter and more open than the other,

and the radius of curvature of the two halves is not equal. The top and outside

are more polished than the interior and bottom, a practice which continues with

Classic Period yokes. Its reported association with a serpentine human figuring

suggests it may date from the late Early to Middle Formative Period (c.

900 B.C.), when use of jade-like greenstone was common. However, the excavators

of the site have documented that the ballgame was played during the Early Formative

(1500=900 B.C.) since rubber balls recovered from that level are of the size

used in the ballgame of both ethnohistoric as well as modern times.

Wooden

sculptures nearby also date to about 1200-900 B.C. The excavators suggest that

a pair of 2-ft (0.6-m) wooden staffs recovered at El Manatí might have been

used as ballgame bats. The El Manatí is similar in its general parallel-sided,

U-shaped configuration to one at Princeton University (fig. 47) said to have

some from Rio Pesquero, Veracruz, a site associated with fine jade full-face

masks. The yoke was crafted of a finely grained greenstone, and was much more

smoothly and regularly carved than the yoke from El Manatí, Like Inca

stonework, its subtly undulating surface makes it seem organic, although it

lacks any recognizable representation. (John F. Scott, “Dressed to Kill: Stone

Regalia of the Mesoamerican Ballgame,” in The Sport of Life and Death: The

Mesoamerican Ballgame, ed. E. Michael Whittington [London: Thames and

Hudson, 2001], 53)

Figure 46:

Figure 47: